Humour me and read on as I tell you a little story, with a little history, set in Biak.

Gua Japeng / Gua BisengJapanese Caves / Grandmother’s Cave; one guide book gave us the former, the other gave a more folky version, citing a rumour about an old woman who lived in the caves prior to WWII.

It is hot when we arrive at the caves. They’re open now for tourists. We got a quick ride up on ojeks (hired motorbikes); it’s sometime approaching midday, in that hot, bright, so-close-to-the-equator sun. Once we’ve paid our entrance fees and given our mark to another guest book, it’s a relief to start walking along the pathway, into the shade.

The path leads into a tropical forest. We move through a soft green light; trees soar upwards, while vines, ferns and plants grow thickly at a more pedestrian level. The path we walk on is about a metre wide, old cement covered with lichen; we pad gently along.

Gua Japeng is just outside of Biak Kota (the island’s biggest town). The caves were of strategic importance in WWII: up at this entrance, they overlook Biak’s airstrip (built during the war); they also tunnel down south-eastwards to the coast, coming out near Bosnik.

On 27 May 1944, American forces landed on the beaches near Bosnik. Japanese soldiers were hidden in the nearby hills and caves, and although the Americans landed easily, they had a weak position and initially had trouble advancing beyond the beach area. It wasn’t until 22 July that they could claim that Japanese resistance had been overcome.

When defeat was perceived, thousands of the Japanese soldiers withdrew and/or hid in the caves. They refused to surrender. Allies threw drums of petrol and hand grenades down the caves’ entrances. The Japanese – maybe six thousand – were incinerated.

(thanks to JCD for pics)

(thanks to JCD for pics)Sometime in the past fifty years, the Japanese government built a memorial at the cave area. Priests cremated the bones that had been gathered.

Today, the memorial is now behind a sunny blue picket fence. The Japanese had installed stone seats so that people could sit and gaze in at the caves’ entrance, but I couldn’t see them and I think they’ve moved. There is, however, a big box that the guide will open for you; inside are bones.

They looked freshly unearthed to me, and whose they are – well, it’s more fun not knowing.

“Gua Japeng”, of course, refers to the Japanese soldiers who lived and died in the caves. It is the term the locals all use, and the sign at the caves’ site. Forget this grandmother business; history is less mediocre, and people are not so weak. Listen to the stories they tell you; there’s mettle in there. Let me tell you another one.

Biak Story # 12 Biak Bloody BiakOn 1 July 1971, a declaration of independence was made by Papuans – independence from Indonesian rule (I’m referring here to West Papuans; not sure what the correct term is). The date remains an unofficial anniversary, marked each year by Papuans; usually marked with caution, for fear of arrest.

In Biak, in 1998, it was different: there was a big public demonstration.* Hundreds of the OPM – Organisasi Papua Merdeka (Free West Papua Movement) – gathered at Biak Kota’s water tower and raised an independence flag. They were public. They were armed, with knives and spears. Local church leaders convinced them to disarm, but the crowd refused to disperse. People stayed there for days.

On 3 July, police and the ABRI – Angkatan Bersenjata Republik Indonesia (Inodnesian Armed Forces) – came down with batons and charged the crowd, who resisted and fought back. 13 soldiers were injured; I’m not sure about the Papuans. The OPM stayed.

Two days later, the police set down a deadline: people had to disperse by 5pm. The crowd didn’t budge; people set in for another night. Additional armed forces were flown in, and marines assembled (Biak Kota is a port town, and two navy frigates were in). At 5:30am on 6 July the crowd was attached. Many people were still asleep.

The official forces open fire, killing 20 Papuans and injuring 141. People were shot in their legs, a “prearranged strategy to inflict maximum terror. The shooting was indiscriminate” (Elmslie 241). Houses in the area were searched and suspected OPM sympathisers were shot on sight.

The people caught were assembled at the water tower. They were forced to lie down; once down, they were rifle-whipped and kicked. They were forced to crawl down to the wharf, and lie back again, now in the fierce sun. For two hours they had to lie as soldiers marched on their faces and stomachs, and beat them. Then they were ordered to crawl to the town jail.

Another 139 people were loaded onto the two naval frigates. This included women and children. The frigates went out to sea. Women were stripped and raped. People were slaughtered. Bodies were chopped into pieces and put in bags; others were thrown overboard.

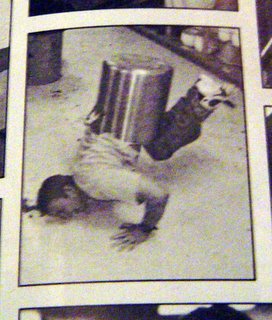

A few kids jumped and swam, saving their lives. One man hid in a barrel and survived. No one else was seen again, alive.

In the following days, bodies washed up on Biak’s shores, or were snarled in fishing nets.

The Indonesian military later reported that one person was killed and two were missing. They explained the bodies that were turning up as being those of victims of a tsunami, which occurred at least a week later (I’m not sure if it was even that same year).

I only read about this later, after I’d left Biak, so I didn’t pay attention to a water tower, if I passed it. In fact, I hardly saw any Papuans in Biak Kota. It was different outside of the town; there were Papuans in the inner parts of the island. On the coastal areas we moved through, though, most people were mixed race; more lighter shades of brown than black. And the kids everywhere were mixed. I’d never read a scrap of information about Bloody Biak. It was someone JCD spoke to who gave the clue; I’m sure that story will appear

over here some time soon; will link properly when it does.

*IRIAN JAYA UNDER THE GUN: Jim Elmslie. 2002. Uni of Hawai’i Press.